LEAD Program Allows Police Officers to Divert Individuals to Resources Instead of Arrest

By Neiman Araque

Charlton Roberson, a Harm Reduction Specialist who works with the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program in Fayetteville, NC, and Cumberland County, said his colleagues working in emergency services or law enforcement often experience compassion fatigue. He explained how repeat offenders often imbue police officers with a sense of hopelessness and despair because of their lack of success as a public servant.

“What difference am I making? What’s the benefit of what I’m doing? With LEAD, [law enforcement and emergency services] can see some of the real benefits of being there to help people and being a public servant,” Roberson added.

He continued, noting that police involvement helps legitimize mental health workers by providing government support while LEAD specialists like Roberson reciprocate legitimacy to police departments by allowing community resources to assist first responders.

Initially launched in 2011, LEAD utilizes a harm-reduction orientation to respond to low-level offenses such as drug possession and prostitution, among others. The aim in doing so is to reduce the number of individuals that enter the criminal justice system by diverting them to treatment instead of arrest. The program was initiated in Seattle, Washington, and involved the collaboration of a range of stakeholders, such as police officers, policymakers, mental health specialists, harm reduction service providers, peer support specialists, and community members.

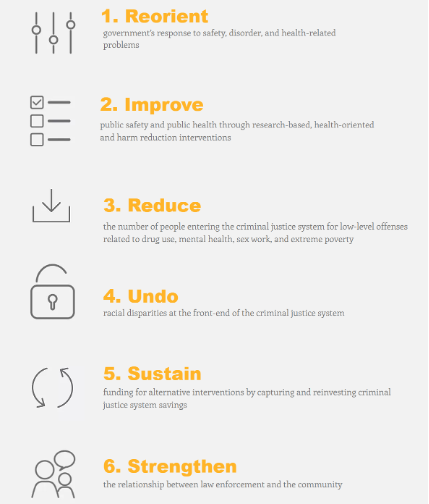

The LEAD National Support Bureau mentions six main goals of LEAD: Reorient, Improve, Reduce, Undo, Sustain, and Strengthen.

The LEAD National Support Bureau mentions six main goals of LEAD: Reorient, Improve, Reduce, Undo, Sustain, and Strengthen.

Additionally, the Bureau provides resources that list the core principles as they apply to certain roles, such as the policing role. The Bureau recommends police departments conduct peer training and support for LEAD, to help legitimize LEAD by allowing police officers to learn about the program from fellow deputies and peers. Another recommendation is that LEAD not be “more onerous than ‘business as usual,’” in that its protocols should not take as much time as it does to arrest someone and enter them through the prosecution process.

Potential participants may engage with LEAD through a referral by a police officer or by a community member. Officers make referrals for individuals who they determine are a good fit for the program and who meet basic eligibility criteria. Community members additionally can provide “social referrals” to police officers. If a community member feels any concern for an individual and believes that they may benefit from a LEAD program, community members may refer police officers to the individual to conduct the assessment process.

If the individual voluntarily accepts the referral, the new participant works closely with case managers to develop a treatment plan based on their situation and needs. Peer specialists such as Roberson serve as “chaperones” for the individual, mentoring the participant throughout their treatment plan and helping them meet their goals. Treatment may include therapeutic services or simply providing them with basic needs such as food and water.

“One of the most rewarding things is to see when someone regains their life and a sense of responsibility over their life, re-establishing relationships, and having a sense of pride and accomplishment,” says Roberson.

Roberson encourages individuals to remember their “monuments,” such as getting a car, getting a job, having children, etc. He compares his philosophy of helping clients to the law of inertia, in that participants should gain enough momentum to move forward so that they can progress with their life. “Many times, individuals are on a downward spiral and lack a sense of self-pride and self-confidence… Helping those individuals gain momentum in the other direction and trying to keep that momentum going [is] a joy to see.”

The LEAD National Support Bureau states the original Seattle LEAD program’s participants were 58% less likely to be arrested after joining the program, in comparison to those who “went through the ‘system as usual’ criminal justice processing.”

Their success may be attributed to the program’s focus on prevention, harm reduction resources, and connection to treatment. LEAD’s approach to alternative policing falls on Intercept 1 of the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM), a community-based model of how the criminal justice system responds to those with mental and substance use disorders. SIM aims to reduce engagement of individuals with the criminal justice system by providing communities with a framework by which to identify gaps, assess the efficacy of programs within each of the intercepts, and more. The model aims to achieve this by involving the community and providing increased availability of resources.

LEAD primarily focuses on Intercept 1 by encouraging police officers to connect citizens with crisis intervention resources and other harm reduction services rather than arresting them. LEAD encourages police officers to refer individuals to mental health experts to improve collaborations between law enforcement and service professionals and connect individuals to needed resources. The redirection away from the criminal justice system ultimately reduces the number of criminalized individuals and improves relations between police officers and members of the community by only utilizing law enforcement when necessary.

LEAD primarily focuses on Intercept 1 by encouraging police officers to connect citizens with crisis intervention resources and other harm reduction services rather than arresting them. LEAD encourages police officers to refer individuals to mental health experts to improve collaborations between law enforcement and service professionals and connect individuals to needed resources. The redirection away from the criminal justice system ultimately reduces the number of criminalized individuals and improves relations between police officers and members of the community by only utilizing law enforcement when necessary.

One researcher who currently studies the efficacy of LEAD, Dr. Allison Gilbert, an Associate Professor in Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, suggests that there are two central components of successful, community-centric police reform: (1) increased availability and access to resources, and (2) clear, effective communication between community stakeholders involved in LEAD programming. This is particularly important in areas where resources are scant.

“[The need for resources to connect people to] seems obvious and so basically important, but many jurisdictions have so few resources that they really struggle in being able to meet their participants’ needs,” says Gilbert, who is also a behavioral health core member at the Wilson Center for Science and Justice at Duke Law.

Gilbert added that allocation of dedicated staff time and funding are also central components of effective police reform, as they equip communities with the tools to streamline the process and maximize the efficiency of connecting individuals to a range of services.

“You have these siloed players… if there’s nobody there that can dedicate staff time to coordinating their work, things can fall away easily,” said Gilbert. “A referral is made and then someone disappears… that can happen often.”

The lack of efficient and effective communication between each stakeholder lengthens the process, providing time barriers between constituents and resources.

Roberson agreed, encouraging community members to reach out and embrace those who are struggling, particularly during the pandemic where social isolation prevails.

“Once a person makes that change, [you should try] to embrace that person, whether it be through employment, spiritual development, or even just association,” he said.

Mental health professionals such as Roberson serve as crucial facilitators in the community effort for improving the lives of individuals. LEAD helps in legitimizing the connections between mental health resources and police officers, and in enabling police officers to serve the community’s needs best.

“As more and more police officers become educated on LEAD and what it does, I think they embrace it and look at it as an asset… they look at my role as important in giving them some kind of trust, building the trust between participants in the community and the police officers,” said Roberson.

Since LEAD’s initial launch in 2011, three police departments exist that are Bureau-certified LEAD programs: Seattle, Santa Fe, and Albany. However, many departments around the nation currently are implementing LEAD either through allocating more funds or implementing LEAD policies. A number of agencies are either exploring, developing, launching, or operating LEAD programs among their own cities.

By increasing the number of these available resources and increasing the collaborative effort between the community and police officers, police departments become positively reformed by building trust between community stakeholders. Communities benefit largely from passionate citizens who want to help others, researchers who provide empirical support, and police departments who coordinate and communicate with service providers. Building trust between these stakeholders creates safer, healthier, and happier communities.

Neiman Araque was a summer intern with the Wilson Center. He attends the University of California, Irvine, and is expected to graduate as part of the class of 2023.